General

Borg, V. (1996). Death of

the night. Geographical Magazine. 68: 56.

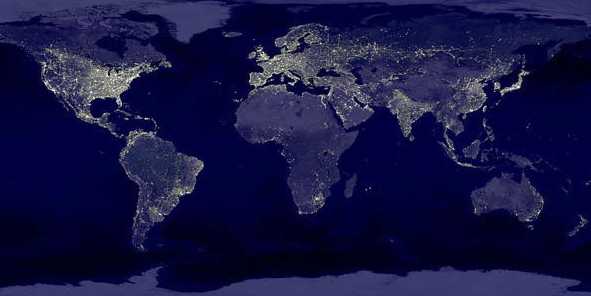

Night light pollution is becoming an increasingly important

environmental problem as well as an impediment to people enjoying

the panorama offered by the stars. Certain animals, such as

sea turtles in the Mediterranean and migratory birds that fly

by night, are disturbed in their reproductive and migratory

habits by the excess light being given off by lit towns and

cities. The answer is to cap night lights to reduce the glare

that is given off into the sky.

Fedun, I. (1995). Fatal

Light Attraction. Journal of Wildlife Rehabilitation

18(3):10-11.

Harder, B. (2002). "Deprived

of darkness: the unnatural ecology of artificial light at night"

Science News 161(16):248-249.

Health Council of the Netherlands.

2000. Impact of outdoor lighting on man and nature. The Hague:

Health Council of the Netherlands. Publication no. 2000/25E.

(www.gr.nl/OVERIG/PDF/00@25E.PDF)

Raevel P. & Lamiot,

F. (1998). Impacts écologiques de l'éclairage

nocturne. Premier Congrès européen sur la

protection du ciel nocturne, June 30-May 1, Cité des

Sciences, La Villette, Paris.

Outen, A. (1998). The

possible ecological implication of artificial lighting.

Hertfordshire, UK: Hertfordshire Biological

Records Centre.

Upgren, A. R. (1996). "Night

blindness: Light pollution is changing astronomy, the environment,

and our experience of nature." The Amicus Journal

Winter:22-25.

Verheijen, F. J. (1958).

"The mechanisms of the trapping effect of artificial light

sources upon animals." Netherlands Journal of Zoology

13:1-107.

Verheijen, F. J. (1985). "Photopollution: Artificial light

optic spatial control systems fail to cope with. Incidents,

causations, remedies." Experimental Biology 1985:1-18.

Plants

Edwards, D. G. W. and Y.

A. El-Kassaby (1996). "The effect of stratification and

artificial light on the germination of mountain hemlock seeds."

Seed Science and Technology 24(2): 225-235.

Germination in mountain hemlock, Tsuga mertensiana (Bong.)

Carr., was investigated using 19 seed sources from British Columbia.

Neither light nor stratification for 28 days had any significant

effect on germination capacity, but light significantly (p less

than or equal to 0.01) reduced germination rate. Stratification

significantly increased germination rate in all seed sources,

although the amount of total variation attributable to this

effect was small. Stratification did not overcome the effect

of light, and it is recommended that seeds should be covered

after sowing in the nursery. All sources, including one from

the interior of the province, germinated relatively uniformly.

No correlations could be found between germination parameters

and age, source elevation and seed weight, but germination capacity

and seed weight were correlated with latitude. No correlation

existed between seed weight and elevation. For most sources,

a test duration of 21 days was adequate for complete germination

even of unstratified seeds. Mountain hemlock seeds should be

stratified before being sown in the nursery, and they should

be covered during the germination phase to exclude light.

Aquatic

Invertebrates

Moore, M.V., S.M. Pierce,

H.M. Walsh, S.K. Kvalvik, and J.D. Lim (2000). Urban light pollution

alters the diel vertical migration of Daphnia. Proceedings

of the International Society of Theoretical and Applied Limnology.

In press.

Pierce, S.M. and M.V. Moore

(1998). Light pollution affects the diel vertical migration

of freshwater zooplankton. Abstract, 1998. Annual Meeting of

the Ecological Society of America, Baltimore, MD.

Peterson, Aili (2001). Night

lights. Science Observer. January-February. Online: http://www.sigmaxi.org/amsci/Issues/Sciobs01/sciobs0101nightlights.html

Terrestrial

Invertebrates

Bhattacharya, A., Y. D.

Mishra, et al. (1995). "Attraction of some insects associated

with lac towards various coloured lights." Journal of

Insect Science 8(2):205-206.

Three different colours of light, i.e., blue, yellow and red

along with natural light has been tested to find out the degree

of photo-attraction of eight insect species found in the biotic

complex around lac insect. All the eight species tested showed

high degree of attraction towards natural light and least for

blue. Marked differences have also been observed in the behaviour

of the predators and parasitoids for yellow and red colour lights.

Craig, C. L. and C. R. Freeman

(1991). "Effects of predator visibility on prey encounter:

A case study on aerial web weaving spiders." Behavioral

Ecology and Sociobiology 29(4):249-254.

Perhaps the most important factor affecting predator-prey interactions

is their encounter probability. Predators must either locate

sites where prey are active or attract prey to them, and prey

must be able to recognize potential and flee before capture.

In this study we manipulate and describe three components of

the foraging system of predatory, web-weaving spiders, the presence

of viscid droplets, silk brightness (achromatic surface reflectance),

and visibility of the orb pattern, to determine their effect

on insect attraction, recognition, and web avoidance. We found

that webs with viscid droplets were more visible to prey at

close range, but at greater distances the sparkling droplets

lured insects to the web area and hence increased insect capture

probability. Although the size of viscid droplets and silk brightness

are closely correlated (Table 2, Fig. 3), the relationships

among droplet size, spider size, and the visual environments

in which webs are found are more complicated (Fig. 2, Tables

2, 3). In environments with predictable light exposure, droplet

size and hence milk visibility correlate with spider size, and

spiders that forage at night produce relatively more visible

silks then spiders that forage during the day (Table 3, Fig.

4). In habitats in which light levels are not predictable, silk

surface reflectance and spider size are not closely correlated,

suggesting that the complexity of the light environment, as

well as the visual and foraging behaviors of insects found there,

has played an important role in the evolution of spider-insect

interactions.

Eisenbeis, G. and F. Hassel

(2000) "[Attraction of nocturnal insects to street lights

- a study of municipal lighting systems in a rural area of Rheinhessen

(Germany.]" Natur und Landschaft 75(4):145-156.

Street lamps which illuminate public areas and places at night

are of different types, emitting different spectra. All of them

(e.g. white mercury (HME), orange sodium (HSE) or sodium-xenon

vapour lamps (HSXT)) attract insects. During summer nights,

myriads of insects fly restlessly around the lamps, which therefore

have a marked impact on insect biology. There is some evidence

that lamps differ with respect to their insect attraction. Sodium

lamps, for instance, attract insects less strongly than white

mercury lamps. We tested the attraction of three lamp types

and, in addition, an ultraviolet absorber foil and some controls

(lights without illumination). All installations were carried

out by the electric utility of Rheinhessen/Germany (EWR) at

three sites in a rural area. To trap insects, we used 19 air-eclector

traps which had been positioned within the light cones of the

street lights. We caught a total of 44,210 insects (including

some arachnids), distributed among 12 orders. Altogether the

data set comprised 536 night trapping records. The results show

that the number of insects captured at the three sites and the

attraction per eclector per day depends significantly on both

the type of lamp and the site. By using sodium vapor street

lamps (HSE), the number of insects caught was reduced signficantly

by more than 50%, and in the case of Lepidoptera by about 75%.

We therefore recommend the use of sodium high pressure vapour

lamps to improve the conservation of insect fauna. The results

further show that there is a large potential to reduce costs

for municipalities by switching street illumination from mercury

vapour (HME) to sodium vapour (HSE) lamps.

Frank, K. D. (1988). "Impact

of outdoor lighting on moths: An assessment." Journal

of the Lepidopterists' Society 42(2):63-93.

Outdoor lighting has sharply increased over the last four decades.

Lepidopterists have blamed it for causing declines in populations

of moths. How outdoor lighting affects moths, however, has never

been comprehensively assessed. The current study makes such

an assessment on the basis of published literature. Outdoor

lighting disturbs flight, navigation, vision, migration, dispersal,

oviposition, mating, feeding and crypsis in some moths. In addition

it may disturb circadian rhythms and photoperiodism. It exposes

moths to increased predation by birds, bats, spiders, and other

predators. However, destruction of vast numbers of moths in

light traps has not eradicated moth populations. Diverse species

of moths have been found in illuminated urban environments,

and extinctions due to electric lighting have not been documented.

Outdoor lighting does not appear to affect flight or other activities

of many moths, and counterbalancing ecological forces may reduce

or negate those disturbances which do occur. Despite these observations

outdoor lighting may influence some populations of moths. The

result may be evolutionary modification of moth behavior, or

disruption or elimination of moth populations. The impact of

lighting may increase in the future as outdoor lighting expands

into new areas and illuminates moth populations threatened by

other disturbances. Reducing exposure to lighting may help protect

moths in small, endangered habitats. Low-pressure sodium lamps

are less likely than are other lamps to elicit flight-to-light

behavior, and to shift circadian rhythms. They may be used to

reduce adverse effects of lighting.

Gerson, E. A. and R. G.

Kelsey (1997). "Attraction and direct mortality of pandora

moths, Coloradia pandora (Lepidoptera: Saturniidae),

by nocturnal fire." Forest Ecology and Management

98(1):71-75.

The attraction of nocturnal moths to candles and other sources

of light has long been observed, but fire as a potential source

of mortality to moths in ecosystems with frequent fire regimes

has been overlooked. A prescribed burn was conducted shortly

after dark in a central Oregon ponderosa pine forest during

the flight period of the endemic defoliator Coloradia pandora

(Blake). Attraction to the fire and partial consumption by flames

caused direct mortality estimated at 2.2% to 17.1% of the local

pandora moth population. In field tests with projected light,

pandora moths did not discriminate among colors in the visible

spectrum. Moths did not respond to projected light for at least

1 h after dusk, indicating that timing and duration of the prescribed

fire may have limited the mortality.

Gotthard, K. (2000). "Increased

risk of predation as a cost of high growth rate: An experimental

test in a butterfly." Journal of Animal Ecology

69(5):896-902.

1. Life history theoreticians have traditionally assumed that

juvenile growth rates are maximized and that variation in this

trait is due to the quality of the environment. In contrast

to this assumption there is a large body of evidence showing

that juvenile growth rates may vary adaptively both within and

between populations. This adaptive variation implies that high

growth rates may be associated with costs. 2. Here, I explicitly

evaluate the often-proposed trade-off between growth rate and

predation risk, in a study of the temperate butterfly, Pararge

aegeria (L). 3. By rearing larvae with a common genetic

background in different photoperiods it was possible to experimentally

manipulate larval growth rates, which vary in response to photoperiod.

Predation risk was assessed by exposing larvae that were freely

moving on their host plants to the predatory heteropteran, Picromerus

bidens (L.). 4. The rate of predation was significantly

higher in the fast-growing larvae. An approximately four times

higher relative growth rate was associated with a 30% higher

daily predation risk. 5. The main result demonstrates a trade-off

between growth rate and predation risk, and there are reasons

to believe that this trade-off is of general significance in

free-living animals. The results also suggest that juvenile

development of P. aegeria is governed by a strategic

decision process within individuals.

Heiling, A. M. (1999). "Why

do nocturnal orb-web spiders (Araneidae) search for light?"

Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 46(1):43-49.

The nocturnal orb-web spider Larinioides sclopetarius lives

near water and frequently builds webs on bridges. In Vienna,

Austria, this species is particularly abundant along the artificially

lit handrails of a footbridge. Fewer individuals placed their

webs on structurally identical but unlit handrails of the same

footbridge. A census of the potential prey available to the

spiders and the actual prey captured in the webs revealed that

insect activity was significantly greater and consequently webs

captured significantly more prey in the lit habitat compared

to the unlit habitat. A laboratory experiment showed that adult

female spiders actively choose artificially lit sites for web

construction. Furthermore, this behaviour appears to be genetically

predetermined rather than learned, as laboratory-reared individuals

which had previously never foraged in artificial light exhibited

the same preference. This orb-web spider seems to have evolved

a foraging behaviour that exploits the attraction of insects

to artificial lights.

Kolligs, D. (2000). "Ecological

effects of artificial light sources on nocturnally active insects,

in particular on butterflies (Lepidoptera)." Faunistisch-Oekologische

Mitteilungen Supplement 28:1-136.

It is a well known phenomena that night-active insects are attracted

by artificial light sources. With a growing urban environment

and a high number of street lamps and other light emitting sources,

the response of night active insects to artificial light becomes

of in-creasing importance for nature protection. This study

focuses on the behavioural response of different insect orders,

families and species to the most frequently used exterior lighting

and street lamps (mercury- and sodium-vapour lamps). These artificial

sources of light distinctly increased in the last decades. In

the city of Kiel (North-Germany) the number of streetlights

was fifty times higher in 1998 than in 1949. The investigations

were carried out at two sites in Schleswig-Holstein (North-Germany):

in Albersdorf / Dithmarschen (western Schleswig-Holstein) and

in Kiel on the university campus (eastern Schleswig-Holstein).

In Albersdorf, the insects were attracted by a light emitting

greenhouse (10,000 m2) and by two punctually radiating light

sources (light traps with mercury and sodium-vapour lamps) and

became comparative investigated in 1994 to 1995. Two different

methods were used to record insects at the greenhouse. Butterflies

(Lepidoptera) were sampled by hand. The remaining insects were

trapped in two 1.5 m2 large sample areas using a suction trap.

Insects from each of the four sides of the green-house were

sampled and trapped separately. The two light traps caught the

insects automatically. On the campus of Kiel University insects

were studied from 1994 to 1996. For this purpose four street

lamps equipped with mercury-vapour lamps had traps attached

to the socket. On one of the four street lamps the mercury-vapour

lamp was exchanged by a sodium-vapour lamp with the same light

intensity. In 1996 two additional street lamps were equipped

with a different type of trap. 72,267 insects from 114 insect

families and 96,725 insects from 138 families were redorded

at Albersdorf and at Kiel, respectively. Butterflies (Lepidoptera),

beetles (Coleoptera), caddies flies (Trichoptera) and sciarid

flies (Sciaridae) were determined to the species level. An analysis

of the catches gave the following resuits: Mosquitos (Nematocera)

made up the majority of all captured insects (40 - 90 %). The

other most conunon groups were butterflies (Lepidoptera), flies

(Brachycera) and beetles (Coleoptera). In both study areas Hymenopterans

(Hymenoptera), aphids (Aphidina), cicadas (Cicadina), true bugs

(Heteroptera), neuropterans (Neuroptera), caddis flies (Trichoptera),

psocids (Psocoptera) and mayflies (Ephemeroptera) made up less

than 1 % of the total catch. Catches from adjacent street lamps

(25 m apart) were distinctly different in their insect compositions.

These differences seem to be caused by the surrounding habitats

and the wind exposure of the lamps. Significant differences

between the compositions of samples from different street lamps

were oniy found between May and the end of August. In spring

and autumn the sample 13 sizes were small and species compositions

were not significantly different. In contrast to hand sampling

not all insects that flew into street lamps were caught by the

automatic light traps (e. g. only 30-40 % of the Lepidoptera

were caught by the traps) No significant correlation was found

between the size of a light source and the number of Lepidoptera

attracted by it. Rather the intensity and the light spectrum

seem to control butterfly abundance at a light source. The light

spectrum of the sodium-vapour lamp attracted fewer species and

individuals than the mercury-vapour lamp. Otherwise from some

species, e.g. he swift mohs (Hepialidae) or the geometric moth

Idaea dimidiata, more individuals were registrated at the sodium-vapour

lamps. Only single individuals of endangered butterfly species

were found at the different light sources, while 31 beetle species

of the Red List of Schleswig-l-Iolstein were captured in the

study area in Kiel.

Klotz, J. H. and B. L. Reid

(1993). "Nocturnal orientation in the black carpenter

ant Camponotus pennsylvanicus Degeer (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)."

Insectes Sociaux 40(1):95-106.

The black carpenter ant Camponotus pennsylvanicus (DeGeer),

a predominantly nocturnal Formicine ant, responds to a hierarchy

of visual and tactile cues when orienting along odor trails

at night. Under illumination from moonlight or artificial light,

workers rely upon these beacons to mediate phototactic orientation.

In the absence of moonlight or artificial lights, ants were

able to orient visually to terrestrial landmarks. In the absence

of all landmarks, save for overhanging tree branches, ants could

negotiate shortcuts or make directional changes in response

to visual landmarks presented within the tree canopy on a moonless

night. When experimental manipulations placed the ants in total

darkness, they could no longer negotiate shortcuts and would

resort to thigmotactic orientation along structural guidelines

to reach a food source. The hierachical organization of these

diverse cues in a foraging strategy is discussed, as well as

their adaptive significance to C. pennsylvanicus.

Sivinski, J. M. (1998).

"Phototropism, bioluminescence, and the Diptera."

Florida Entomologist 81(3):282-292.

Many arthropods move toward or away from lights. Larvae of certain

luminescent mycetophilid fungus gnats exploit this response

to obtain prey. They produce mucus webs, sometimes festooned

with poisonous droplets, to snare a variety of small arthropods.

Their lights may also protect them from their own negatively

phototropic predators and/or be used as aposematic signals.

On the other hand, lights may aid hymenopterous parasitoids

to locate fungus gnat hosts. The luminescence of mushrooms can

attract small Diptera, and might have evolved to aid mechanical

spore dispersal. Among Diptera, bioluminescence is found only

in the Mycetophilidae, but the variety of light organs in fungus

gnats suggests multiple evolutions of the trait. This concentration

of bioluminescence may be due to the unusual, sedentary nature

of prey capture (i.e., use of webs) that allows the 'mimicry'

of a stationary abiotic light cue, or the atypically potent

defenses webs and associated chemicals might provide (i.e.,

an aposematic display of unpalatability).

Summers, C. G. (1997). "Phototactic

behavior of Bemisia argentifolii (Homoptera: Aleyrodidae)

crawlers." Annals of the Entomological Society of America

90(3):372-379.

First instars (crawlers) of Bemisia argentifolii Bellows

& Perring were observed in the field and laboratory to move

upward on plants, presumably in search of acceptable feeding

sites. Laboratory experiments were conducted on a host plant

and an artificial surface to determine if this movement was

random, or a response to light (phototaxis) or gravity (geotaxis).

Greenhouse-reared B. argentifolii crawlers were positively

phototactic in experiments conducted on a host plant and on

an artificial surface of black construction paper. Crawlers

moved up or down the petiole of cheeseweed. Malva parviflora

L., with equal facility, toward a light source placed either

above or below the leaf blade. Response was always toward the

light (positive phototaxis) and there was no response to gravity,

either positive or negative. Crawlers placed on an artificial

surface in a dark arena and presented with a point light source

had a significant mean angular dispersion toward the light.

Crawlers illuminated with uniform overhead lighting or kept

in darkness moved about the arena at random. Crawlers maintained

in darkness on cheeseweed and the artificial surface moved a

significantly shorter distance from their origin than did those

exposed to light. Such behavior suggests that some minimal light

intensity may be necessary to stimulate crawler activity. The

positive phototactic response may contribute to survival of

B. argentifolii by enabling individuals eclosing from

fall laid eggs, on leaves that become senescent during the winter,

to find suitable leaves for development higher on the plant.

Sustek, Z. (1999). "Light

attraction of carabid beetles and their survival in the city

centre." Biologia (Bratislava) 54(5):539-551.

A carabid assemblage attracted on an intensively illuminated

advertisement table above a shop window in the centre of Bratislava

in August and September 1997 consisted of 40 species. This number

was almost the same as in the pitfall trap catches carried out

during three growing seasons in 13 sites in Bratislava. Almost

94% of individuals belonged to autumn breeding species inhabiting

arable land, while the spring breeders were little represented.

Compared with light traps catches performed in other localities

by other authors, there was an increased proportion of Amara

apricaria. In addition the xerotermophilous species Harpalus

tenebrosus and H. zabroides and the rare Polystichus

connexus were found. Three major periods in flight activity

and species composition of the Carabid assemblage were distinguished

according to species abundance and presence. A large number

of Pseudoophonus rufipes, P. calceatus, Dolichus

halensis and Chlaenius spoliatus colonised the study

site. They used various small caves in the walls, gutter pipe

outlets or ants' galleries in the sand between pavement and

wall bases as an effective cover. The beetles exhibited a surprising

ability to survive in the city centre asphalt desert.

Tessmer, J. W., C. L. Meek,

et al. (1995). "Circadian patterns of oviposition by necrophilous

flies (Diptera: Calliphoridae) in southern Louisiana."

Southwestern Entomologist 20(4):439-445.

Circadian ovipositional activities of calliphorid flies on poultry

carcasses were assessed during two 24-h periods in mid-summer

1994 during full (July study) and new moon (August study) phases

in urban habitats with artificial lighting and in rural habitats

without artificial lighting. Immatures of Cochliomyia macellaria

(F.) and Phaenicia sericata (Meigen) were the predominant species

collected during each of the two 24-h field studies. Flies oviposited

during the afternoon diurnal hours and during the morning diurnal

period of the following day of the July and August studies.

However, egg deposition did not occur on any poultry carcass

between the nocturnal hours of 2100 and 0500-h CDST for either

study period regardless of the presence or absence of artificial

or natural (i.e., full moon) lighting.

Amphibians

This section contributed

by Bryant W. Buchanan, Utica College.

Alonso-Gómez, A.

L., N. de Pedro, B. Gancedo, M. Alsonso-Bedate, A. I. Valenciano,

and M. J. Delgado. 1994. Ontogeny of ocular seratonin N-acetyltransferase

activity daily rhythm in four anuran species. General and Comparative

Endocrinology 94:357-365.

Bassinger, S. F. and M. T. Matthes. 1980. The effect of long-term

constant light on the frog pigment epithelium. Vision Research

20:1143-1149.

Baker, J. 1990. Toad aggregations under street lamps. British

Herpetology Society Bulletin 31:26-27.

Beiswenger, R. E. 1977. Diel patterns of aggregative behavior

in tadpoles of Bufo americanus, in relation to light and temperature.

Ecology 58:98-108.

Besharse, J. C. and P. Witkovsky. 1992. Light-evoked contraction

of red absorbing cones in the Xenopus retina is maximally sensitive

to green light. Visual Neuroscience 8:243-249.

Binkley, S. K. Mosher, F. Rubin, and B. White. 1988. Xenopus

tadpole melanophores are controlled by dark and light and melatonin

without influence of time of day. Journal of Pineal Research

5:87-97.

Biswas, M. M., J. Chakraborty, S. Chanda and S. Sanyal. 1978.

Effect of continuous light and darkness on the testicular histology

of toad (Bufo melanostrictus). Endocrinology Japan 25:177-180.

Buchanan, B. W. 1993a. Effects of enhanced lighting of the behaviour

of nocturnal frogs. Animal Behaviour 45:893-899.

Buchanan, B. W. 1999. Low-illumination prey detection by squirrel

treefrogs. Journal of Herpetology 32:270-274.

Bush, F. M. 1963. Effects of light and temperature on the gross

composition of the toad, Bufo fowleri. Journal of Experimental

Zoology 153:1-13.

Chapman, R. M. 1966. Light wavelength and energy preferences

of the bullfrog: evidence for color vision. Journal of Comparative

and Physiological Psychology 61:429-435.

Cornell, E. A. and J. P. Hailman. 1984. Pupillary responses

of two Rana pipiens-complex anuran species. Herpetologica 40:356-366.

Da Silva Nunes, V. 1988. Vocalizations of treefrogs (Smilisca

sila) in response to bat predation. Herpetologica 44:8-10.

Delgado, M. J., P. Gutiérrez, and M. Alsonso-Bedate.

1983. Effects of daily melatonin injections on the photoperiodic

gonadal response of the female frog Rana ridibunda. Comparative

Biochemistry and Physiology 76A:389-392.

D'Istria, M., P. Monteleone, I. Serino, and G. Chieffi. 1994.

Seasonal variations in the daily rhythm of melatonin and NAT

activity in the Harderian gland, retina, pineal gland, and serum

of the green frog, Rana esculenta. General and Comparative Endocrinology

96:6-11.

Donner, K., S. Hemila, and A. Koskelainen. 1998. Light adaptation

of cone photoresponses studies at the photoreceptor and ganglion

cell levels in the frog retina. Vision Research 38:19-36.

Fain, G. L. 1976. Sensitivity of toad rods: dependence on wave-length

and background illumination. Journal of Physiology 261:71-101.

Gancedo, B., A. L. Alonso-Gómez, M. de Pedro, M. J. Delgado,

and M. Alonso-Bedate. 1996. Daily changes in thyroid activity

in the frog Rana perezi: variation with season. Comparative

Biochemistry and Physiology 114C:79-87.

Govardovkii, V. L. and L. V. Zueva, 1974. Spectral sensitivity

of the frog eye in the ultraviolet and the visible region. Vision

Research 14:1317-1321.

Hartman, J. G. and J. P. Hailman. 1981. Interactions of light

intensity, spectral dominance and adaptational state in controlling

anuran phototaxis. Zietschrift für Tierpsychologie 56:289-296.

Hailman, J. P. and R. G. Jaeger. 1974. Phototactic responses

to spectrally dominant stimuli and use of colour vision by adult

anuran amphibians: a comparative survey. Animal Behaviour 22:757-795.

Hailman, J. P. and R.G. Jaeger. 1975. A model of phototaxis

and its evaluation with anuran amphibians. Behaviour 56:215-249.

Hailman, J. P. and R. G. Jaeger. 1978. Phototactic responses

of anuran amphibians to monochromatic stimuli of equal quantum

intensity. Animal Behaviour 26:274-281.

Higginbotham, A. C. 1939. Studies on amphibian activity. I.

preliminary report on the rhythmic activity of Bufo americanus

Holbrook and Bufo Fowleri Hinckley. Ecology 20:58-70.

Jaeger, R. G. 1981. Foraging in optimum light as a niche dimension

for neotropical frogs. National Geographic Society Research

Reports 13:297-302.

Jaeger, R. G. and J. P. Hailman. 1971. Two types of phototactic

behaviour in anuran amphibians. Nature 230:189-190.

Jaeger, R. G. and J. P. Hailman. 1973. Effects of intensity

on the phototactic responses or adult anuran amphibians: a comparative

survey. Zeitschrift für Tierpsychologie 33:352-407.

Jaeger, R. G. and J. P. Hailman. 1976. Ontogenetic shift of

spectral phototactic preferences in anuran tadpoles. Journal

of Comparative and Physiological Psychology 90:930-945.

Jaeger, R. G. and J. P. Hailman. 1976. Phototaxis in anurans:

relation between intensity and spectral preferences. Copeia

1976:92-98.

Jameson, D. and A. Roberts. 2000. Responses of young Xenopus

laevis tadpoles to light dimming: possible roles for the pineal

eye. Journal of Experimental Biology 203:1857-1867.

Joshi, B. N. and K. Udaykumar. 2000. Melatonin counteracts the

stimulatory effects of blinding or exposure to red light on

reproduction in the skipper frog Rana cyanophlyctis. General

and Comparative Endocrinology 118:90-95.

Kicliter, E. and E. J. Goytia. 1995. A comparison of spectral

response functions of positive and negative phototaxis in two

anuran amphibians, Rana pipiens and Leptodactylus pentadactylus.

Neuroscience Letters 185:144-146.

Lee, J. H., C. F. Hung, C. C. Ho, S. H. Chang, Y. S. Lai, and

J. G. Chung. 1997. Light-induced changes in frog pineal gland

N-acetyltransferase activity. Neurochemistry International 31:533-540.

Mahoney, J. J. and V. H. Hutchison. 1969. Photoperiod acclimation

and 24-hour variations in the critical thermal maxima of a tropical

and a temperate frog. Oecologia 2:143-161.

Minucci, S., G. C. Baccari, L. DiMatteo, C. Marmorino, M. D'Istria,

and G. Chieffi. 1990. Influence of light and temperature on

the secretory activity of the Harderian gland of the green frog,

Rana esculenta. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology 95A:249-252.

Morgan, W. W. and S. Mizell. 1971. Daily fluctuations of DNA

synthesis in the corneas of Rana pipiens. Comparative Biochemistry

and Physiology 40A:487-493.

Morgan, W. W. and S. Mizell. 1971. Diurnal fluctuation in DNA

content and DNA synthesis in the dorsal epidermis of Rana pipiens.

Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology 38A:591-602.

Muntz, W. R. A. 1962. Effectiveness of different colors of light

in releasing positive phototactic behavior of frogs, and a possible

function of the retinal projection to the diencephalon. Journal

of Neurophysiology 25:712-720.

Pearse, A. S. 1910. The reactions of Amphibians to light. Proceedings

of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences 45:159-208.

Rand, A. S., M. E. Bridarolli, L. Dries, and M. J. Ryan. 1997.

Light levels influence female choice in Túngara frogs:

predation risk assessment? Copeia 1997:447-450.

Riley, C. F. C. 1913. Responses of young toads to light and

contact. Journal of Animal Behavior 3:179-214.

Steenhard, B. M. and J. C. Besharse. 2000. Phase shifting the

retinal circadian clock: xPer2 mRNA induction by light and dopamine.

Journal of Neuroscience 20:8572-8577.

Sustare, B. D. 1977. Characterizing parameters of response to

light intensity for six species of frogs. Behavioural Processes

2:101-112.

Tárano, Z. 1998. Cover and ambient light influence nesting

preferences of the Túngara frog Physalaemus pustulosus.

Copeia 1998:250-251.

Wright, A. H. and A. A. Wright. 1949. Handbook of Frogs and

Toads of the United States and Canada. Comstock Publishing Company,

Ithaca, NY. pp 167, 169, 188, 314, and 347.

Sea

Turtles

Adamany, S. L., M. Salmon,

et al. (1997). "Behavior of sea turtles at an urban beach:

III. Costs and benefits of nest caging as a management strategy."

Florida Scientist 60(4): 239-253.

At a sea turtle nesting beach in Boca Raton, Florida, all nests

are covered with a wire cage to protect the eggs from beach

traffic and predators. The front panel of the cage (facing the

ocean) is of larger mesh that allows hatchlings to escape. In

this study we determined if cages impede hatchling migration.

No effect was apparent at dark beach sites but at illuminated

beach areas, hatchlings crawled toward lights behind the beach

rather than toward the ocean, and were trapped within the cage.

Trapped turtles eventually escaped, either later that evening

(as lighting was reduced toward midnight) or at dawn (as natural

levels of background illumination increased). However at night,

enough lighting remained to attract turtles after they left

the cage. At dawn, escaped hatchlings crawled to the sea but

were probably vulnerable to visual predators. We conclude that

at urban sites exposed to luminaires, cage use compromises hatchling

survival. Thus at urban rookeries, caging is only effective

if coupled with efforts to eliminate beach-front lighting.

Peters, A. and K. J. F.

Verhoeven (1994). "Impact of artificial lighting on the

seaward orientation of hatchling loggerhead turtles." Journal

of Herpetology 28(1): 112-114.

Salmon, M., R. Reiners,

et al. (1995). "Behavior of loggerhead sea turtles on an

urban beach. I. Correlates of nest placement." Journal

of Herpetology 29(4): 560-567.

Loggerhead sea turtles nesting in Florida sometimes deposit

their clutches on urban beaches. This study was undertaken at

a city beach to determine correlations between physical variables

and where nests were placed. Over a four year period, the distribution

of nests on the beach was statistically identical. Nesting density

variation at particular sites was unrelated to offshore depth

profiles or to beach width, but was strongly correlated with

the presence of tall objects (clusters of mature Australian

pine trees and rows of multi-storied condominiums) located between

the beach and the city. There are no reports that females nest

preferentially in front of tall objects (dune or vegetation)

at natural rookeries. The response may be unique to urban rookeries

where the nesting habitat is exposed to artificial lighting.

Tall buildings and trees shielded the beach from city light,

with the magnitude of the effect (and the number of nests) positively

related to object elevation. Planting vegetation and reestablishing

dunes on urban beaches may be effective methods for attracting

nesting turtles to these sites.

Salmon, M., M. G. Tolbert,

et al. (1995). "Behavior of loggerhead sea turtles on an

urban beach. II. Hatchling orientation." Journal of

Herpetology 29(4): 568-576.

At several locations on an urban nesting beach, loggerhead hatchlings

emerging from their nests did not orient toward the sea. The

cause was city lighting which disrupted normal seafinding behavior.

Observations and experiments were conducted to determine why

females nested where hatchlings were exposed to illumination,

and how hatchlings responded to local conditions. In some cases,

females nested late at night after lights were turned off, but

hatchlings emerged earlier in the evening when lights were on.

In other cases, the beach was shadowed by buildings directly

behind the nest, but was exposed to lights from gaps between

adjacent buildings. In laboratory tests, "urban silhouettes"

(mimicking buildings with light gaps) failed to provide adequate

cues for hatchling orientation whereas natural silhouettes (those

without light gaps) did. Adding a low light barrier (simulating

a dune or dense vegetation) in front of the gaps improved orientation

accuracy. The data show that hatchling orientation is a sensitive

assay of beach lighting conditions, and that light barriers

can make urban beaches safer for emerging hatchlings. At urban

beaches where it may be impossible to shield all luminaires,

light barriers may be an effective method for protecting turtles.

Salmon, M. and B. E. Witherington

(1995). "Artificial lighting and seafinding by loggerhead

hatchlings: Evidence for lunar modulation." Copeia

1995(4): 931-938.

Hatchling sea turtles generally emerge from nests at night and

crawl immediately toward the ocean ("seafinding orientation").

On natural, dark beaches their orientation is usually appropriate,

but where oceanfront buildings are present, hatchlings may crawl

toward artificial lighting behind the beach. A systematic survey

during the 1993 nesting season documented that, on Florida's

beaches, such abnormal behavior ("disrupted orientation")

occurred most often on dark nights around new moon and least

often under full-moon illumination. Experiments on an urbanized

Florida beach (Boca Raton, Palm Beach County) showed that background

illumination from the moon, and not an attraction to the moon

itself, restored normal seafinding orientation. Background illumination

reduced, but did not eliminate, light intensity gradients imposed

by artificial lighting. Thus, when seafinding was restored,

hatchlings moved toward dimmer, not brighter, horizons. These

results suggest that loggerhead hatchlings can locate the sea

using mechanisms other than a positive phototaxis (the most

widely held view). An alternative hypothesis, supported by these

results, is that batchlings locate the ocean by crawling away

from objects behind the beach (dune, vegetation, or buildings)

using shape and/or elevation cues.

Witherington, B. E. and

R. E. Martin (1996). "Understanding, assessing, and resolving

light-pollution problems on sea turtle nesting beaches."

Florida Marine Research Institute Technical Reports 2:

I-IV, 1-73.

Sea turtle populations have suffered worldwide declines, and

their recovery largely depends upon our managing the effects

of expanding human populations. One of these effects is light

pollution - the presence of detrimental artificial light in

the environment. Of the many ecological disturbances caused

by human beings, light pollution may be among the most manageable.

Light pollution on nesting beaches is detrimental to sea turtles

because it alters critical nocturnal behaviors, namely, how

sea turtles choose nesting sites, how they return to the sea

after nesting, and how hatchlings find the sea after emerging

from their nests. Both circumstantial observations and experimental

evidence show that artificial lighting on beaches tends to deter

sea turtles from emerging from the sea to nest. Because of this,

effects from artificial lighting are not likely to be revealed

by a ratio of nests to false crawls (tracks showing abandoned

nesting attempts on the beach). Although there is a tendency

for turtles to prefer dark beaches, many do nest on lighted

shores, but in doing so, the lives of their hatchlings are jeopardized.

This threat comes from the way that artificial lighting disrupts

a critical nocturnal behavior of hatchlings - crawling from

their nest to the sea. On naturally lighted beaches, hatchlings

escaping from nests show an immediate and well-directed orientation

toward the water. This robust sea-finding behavior is innate

and is guided by light cues that include brightness, shape,

and in some species, color. On artificially lighted beaches,

hatchlings become misdirected by light sources, leaving them

unable to find the water and likely to incur high mortality

from dehydration and predators. Hatchlings become misdirected

because of their tendency to move in the brightest direction,

especially when the brightness of one direction is overwhelmingly

greater than the brightness of other directions, conditions

that are commonly created by artificial light sources. Artificial

lighting on beaches is strongly attractive to hatchlings and

can cause hatchlings to move in the wrong direction (misorientation)

as well as interfere with their ability to orient in a constant

direction (disorientation). Understanding how sea turtles interpret

light cues to choose nesting sites and to locate the sea in

a variably lighted world has helped conservationists develop

ways to identify and minimize problems caused by light pollution.

Part of this understanding is of the complexity of lighting

conditions on nesting beaches and of the difficulty of measuring

light pollution with instrumentation. Thankfully, accurately

quantifying light pollution is not necessary to diagnose a potential

problem. We offer this simple rule: if light from an artificial

source is visible to a person standing anywhere on a beach,

then that light is likely to cause problems for the sea turtles

that nest there. Because there is no single, measurable level

of artificial brightness on nesting beaches that is acceptable

for sea turtle conservation, the most effective conservation

strategy is simply to use "best available technology"

(BAT: a common strategy for reducing other forms of pollution

by using the best of the pollution-reduction technologies available)

to reduce effects from lighting as much as practicable. Best

available technology includes many light-management options

that have been used by lighting engineers for decades and others

that are unique to protecting sea turtles. To protect sea turtles,

light sources can simply be turned off or they can be minimized

in number and wattage, repositioned behind structures, shielded,

redirected, lowered, or recessed so that their light does not

reach the beach. To ensure that lights are on only when needed,

timers and motion-detector switches can be installed. Interior

lighting can be reduced by moving lamps away from windows, drawing

blinds after dark, and tinting windows. To protect sea turtles,

artificial lighting need not be prohibited if it can be properly

managed.

Other

Reptiles

Henderson, R.W., and R.

Powell. (2001). "Responses by the West Indian Herpetofauna

to human-induced resources." Caribbean Journal of Science

37(1-2): 41-54. Download

PDF.

Includes discussion and examples of species that exploit the

"night-light niche." See Table 6.

McCoid, M.J., and R.A. Hensley.(1993).

"Shifts in activity patterns in lizards." Herpetological

Review 24(3): 87-88.

Identifies 8 Anolis

species and a skink gathered under porch lights on Cocos Island.

Perry, G. and D.W. Buden

(1999). "Ecology behavior and color variation of the green

tree skink, Lamprolepis smaragdina (Lacertilla: Scincidae),

in Micronesia." Micronesia 31(2): 263-273.

From Results section:

Lamprolepis smaragdina

were active during the daylight hours in all locations. At

non-lighted sites, and at ones where only diffuse lighting

was available at night, we observed no nocturnal behavior.

However, up to three skinks were frequently observed at night

on the brightly lit trees on the Kolonia campus of the College

of Micronesia, Pohnpei. This is the first documented examples

of opportunistic night-light feeding in this species. Animals

were actively feeding on small insects (mainly microlepidoptera)

drawn to the light. Most of these sightings were within two

hours of sunset, but at least two of the observations were

at about midnight, and several just before dawn. No skinks

were observed on any of the adjacent (unlighted) trees at

these times, although as many as four were observed together

on these same trees during the day.

Schwartz, A. and R.W. Henderson

(1991). "Amphibians and reptiles of the West Indies: descriptions,

distributions, and Natural history." University of Florida

Press, Gainsville.

Coins term "night-light

niche" for diurnal lizard species that feed at artificial

lights at night.

Fish

See annotated bibliography

at: http://depts.washington.edu/newwsdot/

Anonymous (2000). Seatrout

vs. Light Nuisance, Scottish Anglers National Association,

http://www.sana.org.uk/light.htm

Anonymous (2000). Artificial

light influences on Halibut Fishes, http://miljolare.uib.no/virtue/newsletter/00_09/curr-holm/more-info/halibut.php?utskrift=1

Contor, C. R. and J. S.

Griffith (1995). "Nocturnal emergence of juvenile rainbow

trout from winter concealment relative to light intensity."

Hydrobiologia 299(3):179-183.

This study examined the relationship between light intensity

and the number of juvenile rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss)

visible to a snorkeler during February in the Henrys Fork of

the Snake River, Idaho, USA. Fish were concealed in the substratum

during daylight. Emergence from concealment was observed from

30 to 80 min after real sunset time and began when stars were

first visible (pyranometric irradiance, 4.5 times 10-3 W-2).

Densities of visible fish were negatively correlated with light

intensity (r-2 = 0.81, P < 0.001). Later at night, densities

decreased in the presence of moonlight and artificial light.

Fish were observed to feed at night.

Croze, O., M. Chanseau,

et al. (1999). "Efficiency of a downstream bypass for Atlantic

salmon (Salmo salar L.) smolts and fish behaviour at

the Camon hydroelectric powerhouse water intake on the Garonne

river." Bulletin Francais de la Peche et de la Pisciculture

353-354:121-140.

Three experiments were conducted from 1996 to 1998 at the Camon

hydroelectric powerhouse water intake, on the Garonne River,

to test the efficiency of a surface downstream bypass for Atlantic

salmon smolts. This bypass was built into the trashrack itself

at its left edge. The efficiency of the device was evaluated

using the mark-recapture method. Smolt behaviour in the intake

canal was studied using radiotelemetry technique. In 1996, the

bypass efficiency was low (34%). Radio-tracking showed that

the bypass location was not responsible for its low efficiency,

fish being listened most of the time in the vicinity of the

bypass. Nevertheless, an unstable upwelling hided the device

entrance. After installing submerged horizontal screen and plates

upstream bypass entrance gate, the average efficiency increased

to 73%. Good hydraulic conditions in the intake canal and good

local hydrodynamic in the vicinity of the bypass entrance are

essential to obtain a satisfactory downstream bypass efficiency.

Intermittent nocturnal lighting has an effect on smolt behaviour

in the intake canal by maintaining fish in directly lighted

areas and on the rhythm of fish entry in the bypass, more fish

being captured during the first part of the lighting off period.

The catching of 7,715 wild salmonids has permitted to study

downstream migration rhythms at dam. Daily downstream migration

peaks seems to be linked with high water discharge and/or an

increase of water temperature. Moreover, downstream migration

activity at a dam appears to be mainly nocturnal.

Haymes, G. T., P. H. Patrick,

et al. "Attraction of fish to mercury vapor light and its

application in a generating station forebay." Internationale

Revue der Gesamten Hydrobiologie 69(6): 867-876.

Laboratory and field tests were conducted to determine the effectiveness

of filtered mercury vapor lights in attracting fish with possible

utilization in a fish conserving scheme at an electrical generating

station. In laboratory tests, alewife demonstrated an attraction

to the mercury vapor light which was associated with an increase

in swimming activity. This response was maintained over a 48

h period. When the filtered mercury vapor lights were utilized

in association with a fish pump in the Nanticoke Generating

Station forebay, juvenile gizzard shad and smelt were attracted

to the pump area. Although there was variation with time of

day, turbidity and lighting array, the results suggested that

the number of fish passing through the pump increased when the

mercury lights alone or when the mercury lights in association

with a white strobe light were employed.

Korkosh, V. V. (1992). "Behavior

of Atlantic saury and features of its response to light."

Voprosy Ikhtiologii 32(4):132-137.

The behavior of Atlantic saury was studied in an artificial

light environment. It is found that the response of the fish

to light varies during the year and is determined by biological

and ecological factors. The effectiveness of attraction of the

fish to light depends on the power and spectral characteristics

of light sources. A suggestion is made to use xenon bulbs DKST-20,000.

It is established that attraction to light in Atlantic saury

is based on the food procurement factor.

Larinier, M. and S. Boyer-Bernard

(1991). "Downstream migration of smolts and effectiveness

of a fish bypass structure at Halsou Hydroelectric Powerhouse

on the Nive River." Bulletin Francais de la Peche et

de la Pisciculture 321:72-92.

Downstream migration of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) smolts

in river Nive South-West France was studied in 1987 and 1988

to access the effectiveness of a fish bypass structure at the

hydroelectric plant of Halsou. Passage of fish was determined

by trapping and video recording. Daily, diurnal and hourly passages

at bypass were determined. Tests with marked fish showed between

42% and 95% of the smolts used the surface bypass. Significantly

more smolts were bypassed when the discharge was increased.

Exploratory tests with halogen and mercury lights were performed.

Visual observation indicated that fish was attracted to the

lights but avoided the point source: results showed an increased

rate of passage when the lamps lighting up the bypass were turned

off.

Larinier, M. and S. Boyer-Bernard

(1991). "Smolts downstream migration at Poutes Dam on the

Allier River: Use of mercury lights to increase the efficiency

of a fish bypass structure." Bulletin Francais de la

Peche et de la Pisciculture 323:129-148.

Downstream migration of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) smolts

was studied in 1989 at Poutes dam on the Allier river [France]

to evaluate the effectiveness of mercury lights in modifying

behavioral responses of smolts at a fish bypass structure. Daily

and hourly passage of smolts was accessed by video recording.

Migratory activity was mainly nocturnal, diurnal movements increasing

at the end of emigration period. Analysis of results showed

that the lights significantly increased the rate of passage.

Visual observation showed that illumination duration, light

location and intensity may be important parameters in effective

application of mercury lights for attraction. The effect of

lights was not immediate : the maximum passage rate was observed

more than half an hour following the activation of lights. Three

to eight times as many fish were bypassed with the lights on

than with the lights off.

Larinier, M. and S. Boyer-Bernard

(1991). "Downstream migration of smolts and effectiveness

of a fish bypass structure at Halsou Hydroelectric Powerhouse

on the Nive River." Bulletin Francais de la Peche et

de la Pisciculture 321:72-92.

Downstream migration of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) smolts

in river Nive South-West France was studied in 1987 and 1988

to access the effectiveness of a fish bypass structure at the

hydroelectric plant of Halsou. Passage of fish was determined

by trapping and video recording. Daily, diurnal and hourly passages

at bypass were determined. Tests with marked fish showed between

42% and 95% of the smolts used the surface bypass. Significantly

more smolts were bypassed when the discharge was increased.

Exploratory tests with halogen and mercury lights were performed.

Visual observation indicated that fish was attracted to the

lights but avoided the point source: results showed an increased

rate of passage when the lamps lighting up the bypass were turned

off.

Munday, P. L., G. P. Jones,

et al. (1998). "Enhancement of recruitment to coral reefs

using light-attractors." Bulletin of Marine Science

63(3):581-588.

Methods that enhance larval settlement are required to examine

the importance of recruitment in the dynamics of coral reef

fish populations. Although it is known that larval reef fishes

are attracted to light, here we show for the first time that

a light-attraction device positioned above patch reefs at Lizard

Island (Great Barrier Reef) significantly increased the number

of fish settling on the reefs below. The device was a modified

light trap with a tube allowing the vertical movement of larvae

from the trap to the reef. The number of species of settling

fishes, and the abundance and diversity of immigrant fishes

were also greater on the light-enhanced reefs. By comparison,

the alternative technique of enhancing recruitment using surface

buoys moored to reefs was unsuccessful. Further studies are

now required to determine whether enhanced recruitment using

light-attractors leads to a longer-term increase in population

size, as opposed to temporarily concentrating juveniles on the

reef.

Nemeth, R. S. and J. J.

Anderson (1992). "Response of juvenile coho and chinook

salmon to strobe and mercury vapor lights." North American

Journal of Fisheries Management 12(4):684-692.

Species-specific responses to flashing (strobe) and nonflashing

(mercury vapor) lights were monitored in hatchery-reared juveniles

of coho salmon Oncorhynchus kisutch and chinook salmon O. tshawytscha.

Fish behaviors were characterized as attraction and avoidance

responses, and as active, passive, and hiding behaviors. We

investigated how basic fish behavior and activity changed when

fish held under a variety of ambient light conditions were exposed

to strobe and mercury light. Implications of how these behaviors

may influence migrating smolts at a fish bypass system were

discussed. Both chinook and coho salmon avoided strobe and full-intensity

mercury light, but chinook salmon exhibited an attraction to

dim mercury light. Coho and chinook salmon showed different

behavior patterns under most conditions when exposed to strobe

and mercury light: coho salmon hid 47% of the time, whereas

chinook salmon swam actively 74% of the time. The greatest change

produced by either of the stimulus lights was at night when

both species normally were passive; exposure to mercury light

at nighttime increased fish activity by 90%. Both species also

showed similarities in their levels of exictability (e.g., sudden

or explosive movements in otherwise sedentary behaviors). The

results of this study showed that the behaviors were reproducible:

more than 80% of the fish exhibited the same behavior during

specific environmental conditions, and sudden and infrequent

behaviors were strongly associated with these behavior categories.

The behaviors observed in our experimental environment may give

insight as to how changes in light relate to fish behavior in

bypass systems.

Fritzsche, R.A., R.H. Chamberlain,

and R.A. Fisher. 1985. Species profiles: life histories and

environmental requirements of coastal fishes and invertebrates

(Pacific Southwest) -- California grunion. U.S. Fish Wildl.

Serv. Biol. Rep. 82(11.28) U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, TR

L-82-4. 12 pp.

"Exposure to light

seems to reduce hatching success of grunion eggs (Hubbs 1965).

Young grunion are positively phototactic and can be attracted

to light as bright as 10,000 lux (Reynolds et al. 1977). The

strength of the gathering response is apparently related to

the strength of the

light stimulus."

Hubbs, C. 1965. Developmental

temperature tolerance and rates of four southern California

fishes, Fundulus parvipinnis, Atherinops

affinis, Leuresthes tenuis, and Hypsoblennius

sp. California Fish and Game 51(2):113-122.

From abstract: "California

killifish eggs hatch more slowly in total darkness while light

seems to kill California Grunion eggs."

Reynolds, W. W., D. A. Thompson,

and M. E. Casterlin. 1977. Responses of young California grunion,

Leuresthes tenuis, gradients of temperature and light.

Copeia 1977(1):144-149.

Birds

For collision with tall

lighted structures see also online bibliography Bird

kills at towers and other man-made structures: an annotated

partial bibliography (1960-1998)

Avery, M. , Springer, P.F.,

Cassel, J.F. (1976). "The effects of a tall tower on nocturnal

bird migration - A portable ceilometer study." Auk

93:281-291.

Backhurst, G. C. and D.

J. Pearson. (1977). "Ethiopian region birds attracted to

the lights of Ngulia Safari Lodge, Kenya." Scopus

1(4):98-103.

Baldwin, D.H. (1965). "Enquiry

into the mass mortality of nocturnal migrants in Ontario."

The Ontario Naturalist 3(1):3-11.

Bergen, F. and M. Abs (1997).

"Etho-ecological study of the singing activity of the blue

tit (Parus caeruleus), great tit (Parus major)

and chaffinch (Fringilla coelebs)." Journal fuer

Ornithologie 138(4):451-467.

The main objective of this study was to determine the extent

of influence that a large city's ecological conditions have

on the singing behaviour of urbanised birds. The singing activity

of selected bird species was examined using the "animal

focus sampling" method. The observations were carried out

from the beginning of March to the beginning of June 1995 in

a 10 ha inner city park, the Westpark (WP) in Dortmund (NRW,

Germany). An area of equal size in a forest south of Dortmund,

the Niederhofer Wald (NW) was chosen as a control area. In

the Westpark the Blue Tit, Great Tit and Chaffinch started to

sing significantly earlier in the morning than in the control

area. This difference could be due to the artificial lighting

of the park at night as well as the noise of traffic. There

was no difference in the three species' singing activities between

the two areas, but there were differences in the temporal pattern

of the Chaffinch's morning singing activity in comparison of

the two areas. In the Niederhofer Wald the Chaffinch was almost

equally active at all times whereas it showed a pattern similar

to the Tit's "dawn chorus" in the Westpark. Food supply,

distribution and predictability within the two areas are discussed

as causes for this difference. However, the negative correlation

between singing activity and the frequency of pedestrians crossing

the birds' territories may also play a role. In the Westpark,

a correlation between the Chaffinch's singing activity and the

frequency of passing pedestrians was noted. The more people

crossed the focus animal's territory, the less its singing activity

and the more frequently "pinks" occurred. Thus, pedestrians

do indeed disturb the Chaffinch which reacts with a change of

singing behaviour.

Bretherton B.J. (1902).

"The destruction of birds by lighthouses." Osprey

1:76-78

Bruderer, B., D. Peter,

et al. (1999). "Behaviour of migrating birds exposed to

X-band radar and a bright light beam." Journal of Experimental

Biology 202(9):1015-1022.

Radar studies on bird migration assume that the transmitted

electromagnetic pulses do not alter the behaviour of the birds,

in spite of some worrying reports of observed disturbance. This

paper shows that, in the case of the X-band radar 'Superfledermaus',

no relevant changes in flight behaviour occurred, while a strong

light beam provoked important changes. Large sets of routine

recordings of nocturnal bird migrants obtained using an X-band

tracking radar provided no indication of differing flight behaviour

between birds flying at low levels towards the radar, away from

it or passing it sideways. Switching the radar transmission

on and off, while continuing to track selected bird targets

using a passive infrared camera during the switch-off phases

of the radar, showed no difference in the birds' behaviour with

and without incident radar waves. Tracking single nocturnal

migrants while switching on and off a strong searchlight mounted

parallel to the radar antenna, however, induced pronounced reactions

by the birds: (1) a wide variation of directional shifts averaging

8 degree in the first and 15 degree in the third 10 s interval

after switch-on; (2) a mean reduction in flight speed of 2-3

m s-1 (15-30 % of normal air speed); and (3) a slight increase

in climbing rate. A calculated index of change declined with

distance from the source, suggesting zero reaction beyond approximately

1 km. These results revive existing ideas of using light beams

on aircraft to prevent bird strikes and provide arguments against

the increasing use of light beams for advertising purposes.

Cochran, W.. W. and R. R.

Graber (1958). "Attraction of nocturnal migrants by lights

on a television tower." Wilson Bulletin 70(4):378-380.

Derrickson, K. C. (1988).

"Variation in repertoire presentation in northern mockingbirds."

Condor 90(3):592-606.

Male Northern Mockingbirds (Mimus polyglottos) have exceptionally

large vocal repertoires. The manner of presenting this extensive

repertoire, as described using five measures, varied with reproductive

stage, among situations, and among individuals. All three versatility

measures peaked during courtship declined significantly during

incubation, and then slowly increased during nestling and fledgling

stages. A fourth measure, bout length, increased as the season

progressed, being shortest during courtship and longest during

the fledgling stage. A final measure, recurrence interval (number

of intervening bouts between two bouts of a particular song

type) was shorter during the nestling and fledging stages than

during courtship. Recurrence interval was shortest during patrolling

and countersinging with neighboring males. Over 25% of the song

types occurred only once in the sampling of singing behavior

of four males each over 2 years. Mockingbirds sang these rare

song types most commonly during prefemale and courtship stages,

thereby increasing the recurrence interval and versatility during

these stages. The pattern just described resulted in the greatest

number of song types being sung per unit of time during courtship

and provide circumstantial support for the hypothesis that song

functions intersexually in mockingbirds. The ability to alter

the manner of presentation may provide mockingbirds with the

flexibility to emphasize particular functions at certain times

and other functions at other times. Males with the highest versatility

measures and lowest bout length tended to be the first to acquire

mates and begin to nest. However, the importance of versatility

in attracting females remains speculative and requires further

experimental testing because these results were from only four

males. Songs sung at night were presented in a manner most similar

to the period before a female arrived on a male's territory.

Interestingly, under natural lighting conditions, only unmated

males sang extensively at night.

Frey, J. K. (1993). "Nocturnal

foraging by Scissor-Tailed Flycatchers under artificial light."

Western Birds 24(3):200.

Gorenzel, W. P. and T. P.

Salmon (1995). "Characteristics of American Crow urban

roosts in California." Journal of Wildlife Management

59(4):638-645.

American crows (Corvus brachyrhynchos) roost in urban areas

across the United States creating problems resulting from fecal

droppings, noise, and health hazards. With little information

about roosts, managers have been unable to respond to questions

from the public about roost problems or design control programs.

We counted crows flying into Woodland, California, to roost,

surveyed roosts for occupancy, and recorded features of 87 roost

trees and 62 randomly selected nonroost trees from August 1992

through July 1994. Some crows roosted in town all year, with

peak abundance from September through January. Roost trees had

greater height, diameter at breast height (dbh), and crown diameter

and volume than nonroost trees (P < 0.001 all cases). Most

roost trees were located over an asphalt or concrete substrate

(P < 0.001) in commercial areas of the city, rather than

in residential areas (P < 0.001), and were subjected to greater

disturbance from vehicles and people (P < 0.01). Ambient

light levels and interior canopy temperatures during winter

were greater at roost trees than nonroost trees (P < 0.001

both cases). There were seasonal changes in roost trees

selected with an increased (P < 0.001) use of deciduous trees

(elms (Ulmus spp.), mulberries (Morus spp.), oaks

(Quercus spp.), and ashes (Fraxinus spp.)) in

residential areas during summer months as opposed to the concentrated

use of evergreen oaks, alders (Alnus spp.), and conifers

(Pinus spp. and Sequoia spp.) in commercial areas

during winter. We developed a logistic regression model with

4 variables that correctly classified status of 85% of roost

or nonroost trees.

Hill, D. 1992. The impact

of noise and artificial light on waterfowl behavior: a review

and synthesis of available literature. British Trust for

Ornithology Research Report No. 61.

Hoetker, H. (1999). "What

determines the time-activity budgets of avocets (Recurvirostra

avosetta)?" Journal fuer Ornithologie 140(1):57-71.

Time-activity budgets of birds are known to be affected by many

different factors. The aim of this study is to explain the intra-specific

variation of activity patterns (in particular foraging activity)

of one particular wader, the Avocet. Sixty-seven series of scan

observations of 12 h to 12.5 h length were made at several sites

on the flyway of the northwest European population and at various

stages in the species' annual cycle. In estuarine habitats the

activity pattern was mainly influenced by the tide. As soon

as the conditions allowed (neap tides) Avocets abandoned the

tidal rhythm. No time of day effects on activity patterns could

be detected. Activity patterns by day and at night were essentially

the same, except during very dark nights (owing to artificial

illumination at some of the study sites such nights were a rare

event), when foraging activity was reduced. The breeding

season induced considerable changes of the activity patterns,

including a reduction of foraging time to less than 20% of the

budget at the end of the breeding season. Outside the breeding

season, activity patterns were mainly influenced by the type

of food (fish: reduced foraging time, Chironomid larvae: prolonged

foraging time), by temperature (increase of foraging time with

decreasing temperature), by windspeed (reduction of foraging

time at wind speeds above 10 m/s) and by the darkness of the

previous night (compensatory feeding after dark nights).

Manville, Albert M., II.

(2000). "The ABCs of avoiding bird collisions at communication

towers: the next steps." Proceedings of the Avian Interactions

Workshop, December 2, 1999, Charleston, SC. Electric Power Research

Institute.

Published accounts of avian collisions with tall, lit structures

date back in North America to at least 1880. Long-term studies

of the impacts of communication towers on birds are more recent,

the first having begun in 1955. This paper will review the known

and suspected causes of bird collisions with communication towers

(e.g., lighting color, light duration, and electromagnetic radiation),

assess gaps in our information base, discuss what is being done

to fill those gaps, and review the role of the U.S. Fish and

Wildlife Service (FWS or Service) in dealing with this important

problem. This paper will also review avian vulnerability to

collisions with tall structures, currently affecting nearly

350 species of neotropical migratory songbirds that breed in

North America in the spring and summer and migrate to the southern

United States, the Caribbean, or Latin America during the fall

and winter. These species generally migrate at night and appear

to be most susceptible to collisions with lit towers when foggy,

misty, low-cloud-ceiling conditions occur during their spring

and fall migrations. Thrushes, Vireos, and Warblers are the

species that seem the most vulnerable. Lit towers, those exceeding

199 feet (61 m) above the ground, currently number about 46,000

in the United States (not including lit "poles"),

with the total number of towers registered in the Federal Communications

Commission database listed at some 75,000. Also included in

this paper are preliminary voluntary recommendations designed

to help minimize bird collisions with towers, as well as a review

of activities that prompted recent FWS action in dealing with

this issue. This paper will further review two partnerships

with the electric utility and electric wind generation industries

- the Avian Power Line Interaction Committee and the National

Wind Coordinating Committee's Avian Subcommittee, respectively

- as possible models for a future partnership with the communication

industry (i.e., radio, television, cellular, and microwave).

Miller, R. (1998). "Flocks

of crows making urban areas home, so look out below." The

News-Times, December 28. [online at: http://www.newstimes.com/archive98/dec2898/lcd.htm].

Negro, J. J., J. Bustamante,

et al. (2000). "Noctural activity of Lesser Kestrels under

artificial lighting conditions in Seville, Spain." Journal

of Raptor Research 34(4):327-329.

Nein, R. "A Robin uses

artificial light for feeding at night." Beitraege zur

Naturkunde der Wetterau 9(2):213.

Nikolaus, G. 1980. An Experiment

to Attract Migrating Birds with Car Headlights in the Chyulu

Hills, Kenya. Scopus 4(2):45-46. .

Nikolaus, G. and D.J. Pearson.

1983. Attraction of Nocturnal Migrants to Car Headlights in

the Sudan Red Sea Hills. Scopus 7(1):19-20.

Ogden, L. J. E. (1996).

Collision course: the hazards of lighted structures and windows

to migrating birds. Toronto, World Wildlife Fund Canada

and Fatal Light Awareness Program.

Seabirds

Ainley, D. G., R. Podolsky,

et al. (1997). "New insights into the status of the Hawaiian

Petrel on Kauai." Colonial Waterbirds 20(1):24-30.

We present new information, on the basis of observations and

an analysis of existing but unpublished data, regarding the

present status of the Hawaiian Petrel on Kauai. A consistently

used rafting area just offshore of Hanalei, on the north shore

of Kauai, is described for the first time. Observations made

there in June and July 1993 and 1994, indicate that the population

frequenting breeding colonies, on the order of gt 1000 birds

per night during the peak of the visitation cycle, is much larger

than previously thought. In contrast, few sightings of this

species were made elsewhere around the island. Corroborating

these observations were records collected by state and federal

biologists on fledglings attracted to lights during their initial

flight, 1980-1993, indicating a virtual confinement of the population

to the north shore. Data presented also indicate that the nesting

season on Kauai maybe a few weeks later than on Maui, the only

locale where extensive research has been conducted on this species.

On Kauai, increasing numbers of Hawaiian Petrel fledglings are

being found each year. We propose that this is a result of the

increasing numbers of coastal lights, and not an increase in

the petrel's population. The increasing numbers found have implications

for conservation of this species' population on Kauai.

Bertram, D. F. (1995). "The

roles of introduced rats and commercial fishing in the decline

of ancient murrelets on Langara Island, British Columbia."

Conservation Biology 9(4): 865-872.

I examined the decline of Ancient Murrelets (Synthliboramphus

antiquus), a small, burrow-nesting seabird, at Langara Island.

The island's seabird colony was historically one of the largest

colonies of Ancient Murrelets in British Columbia-perhaps in

the world-with an estimated 200,000 nesting pairs. I reviewed

historical information and compared the results of surveys from

1981 and 1988 that employed the same census protocol. The extent

of the colony, a potential index of population size, declined

from 101 ba in 1981 to 48 ha in 1988. Burrow density increased

during the same period, however, suggesting that the colony

bad consolidated. In 1988, the population estimate was 24,200

plus-minus 4000 (S.E.) breeding pairs compared to 22,000 plus-minus

3700 in 1981. In 1988, 29% of the burrows that were completely

searched contained bones of Ancient Murrelets. Bones were most

common in burrows located in abandoned areas of the colony and

were least common where burrow occupancy was high. The discovery

of adult Ancient Murrelets killed in their burrows by introduced

rats, combined with the high proportion of burrows with bone,

suggests that rats (Rattus rattus and R. norvegicus)

have contributed significantly to the decline of the population.